Plant Toxin Causes Biliary Atresia in Animal Model, According to Penn Study

A study in this week’s Science Translational Medicine is a classic example of how seemingly unlikely collaborators can come together to make surprising discoveries. An international team of gastroenterologists, pediatricians, natural products chemists, and veterinarians, working with zebrafish models and mouse cell cultures have discovered that a chemical found in Australian plants provides insights into the cause of a rare and debilitating disorder affecting newborns. This ailment, called biliary atresia (BA), is the most common indication for a liver transplant in children.

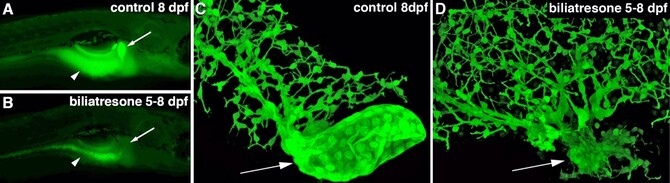

The team isolated a plant toxin with a previously uncharacterized chemical structure that causes biliary atresia in zebrafish and mammals, noted collaborators Michael Pack, MD, a professor of Medicine in the Gastroenterology Division and the department of Cell and Developmental Biology, and Rebecca Wells, MD, an associate professor of Medicine in the Gastroenterology Division and the department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, both at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

BA is a rapidly progressive and destructive disorder that affects the cells lining the extra-hepatic bile duct. The cells within this large duct, which carries bile from the liver to the small intestine, are damaged as the result of an as-yet-unidentified environmental insult, a toxin or infection, resulting in scarring (fibrosis) that obliterates the duct, thus preventing bile flow.

The incidence of BA is 1/10,000 to 15,000 live births. It occurs worldwide and is one of the most rapidly progressive forms of liver cirrhosis and liver failure. Fortunately, a life-saving treatment for BA is available for babies, a surgical procedure called a Kasai portoenterostomy, in which a small segment of intestine is connected directly to the liver, to restore bile flow. Most babies, though, eventually develop cirrhosis of the liver and ultimately liver failure, leading to the need for a transplant either in infancy, childhood or adolescence.

Working with pediatric gastroenterologists Elizabeth Rand, MD and David Piccoli, MD and other colleagues at the Fred and Suzanne Biesecker Pediatric Liver Center at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Pack and Wells became interested in a naturally occurring BA model reported by veterinarians in Australia. During years of extreme drought over the last four decades, sheep and cows grazed in unusual pastures had given birth to offspring with a BA-like syndrome that was essentially identical to human BA. Field veterinarian Steve Whittaker, BVSc, and veterinary scientist Peter Windsor, DVSc, PhD, who diagnosed BA in lambs during a drought in 2007, correlated the outbreaks with ingestion of plants in the genus Dysphania, including a plant called pigweed, that grew on lands normally under water, suggesting a toxic cause of the animal BA

“The 2007 drought persisted through 2008, enabling us to harvest Dysphania species plants from a pasture implicated in the 2007 episode,” recalls Wells, who initiated the collaboration by contacting Whittaker soon after the 2007 outbreak and arranged to have the plant harvested and imported into the U.S. “With the plant in hand, we knew we had a chance to identify the responsible biliary toxins, guided by a zebrafish bioassay devised in my laboratory,” adds Pack.

Click here to view the full release.