Penn Study Describes a Better Animal Model to Improve HIV Vaccine Development

Vaccines are usually medicine’s best defense against the world’s deadliest microbes. However, HIV is so mutable that it has so far effectively evaded both the human immune system and scientists’ attempts to make an effective vaccine to protect against it. Now, researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania have figured out how to make a much-improved research tool that they hope will open the door to new and better HIV vaccine designs. George M. Shaw, MD, PhD, a professor of Hematology/Oncology and Microbiology, and Hui Li, MD, a research assistant professor of Hematology/Oncology, published their results in the early online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

An ideal preventive vaccine works by presenting non-infectious components or a weakened form of a microbe to the host’s immune cells to prime the system for future contact with the invader. This allows the immune system to mount an attack against a microbe it has already seen.

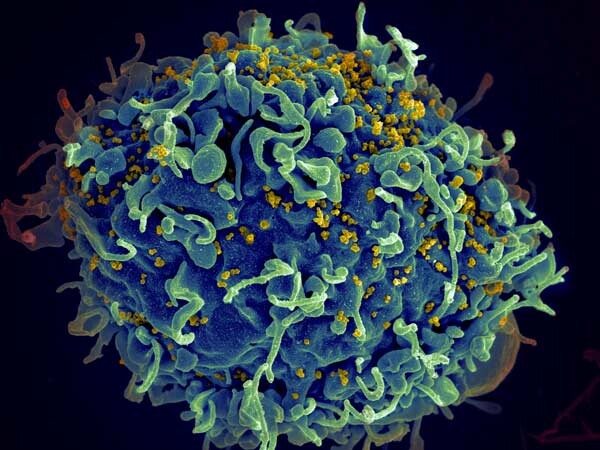

But in the case of fighting AIDS, HIV’s ability to rapidly mutate, especially its outer coat protein -- the envelope -- poses a special challenge to vaccine development. So too does the fact that the envelope is coated with host derived sugars that the human immune system cannot recognize as foreign. These and other features of HIV have stymied vaccine development for over 30 years.

Despite these obstacles, substantial progress in HIV vaccine development has been made, and a number of promising candidate vaccines are in development. However, still another hurdle to progress has been the absence of a good animal model in which to test HIV vaccines. The immune systems of small animals like mice, rabbits, and guinea pigs are too different from the human immune system to be helpful.

Rhesus monkeys are primates whose immune system is much closer to that of humans, but HIV cannot infect or replicate in monkeys. To overcome this obstacle, researchers developed chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIVs), genetically engineered viruses containing the envelope of HIV but with other viral components from simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), which naturally infects monkeys. SHIVs thus seemed to have the best of both worlds: They carried the envelope of HIV and they replicated in monkeys, causing AIDS-like disease.

But there was still one catch -- one unforeseen problem with SHIVs. The only HIV envelopes that would allow SHIVs to infect rhesus monkeys were those that were adapted in artificial ways to bind to the rhesus CD4 molecule, the primary receptor for HIV. As a byproduct of this adaptation, the SHIVs lost their natural defenses to antibodies. This rendered the SHIVs of little value to HIV vaccine research.

Now, Shaw, Li, and their colleagues have found a way to overcome these obstacles and to make a much better SHIV – one that closely mimics HIV infection in humans.

Click here to view the full release.