Penn Sociologist Tackles Electronic Health Records, Cybersecurity and Passwords

More than 90 percent of acute care hospitals and more than 75 percent of office-based physicians use electronic health records, or digital versions of patient charts, typically referred to as EHRs.

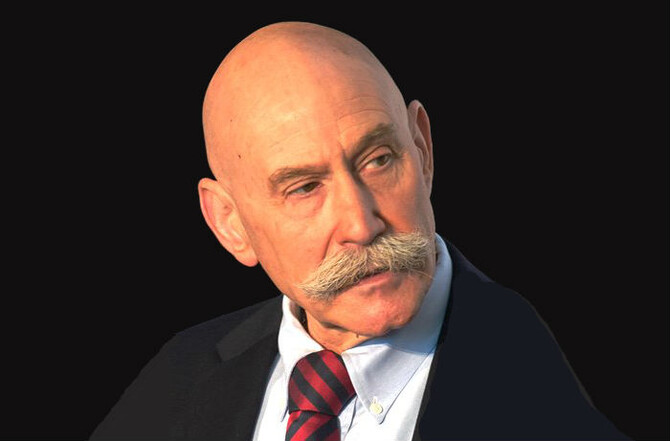

So when University of Pennsylvania sociologist Ross Koppel published a paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association concluding that, in addition to solving some problems, EHRs actually cause 22 types of medication errors, most in the industry didn’t respond too kindly. The medical community, however, took note.

The Journal of Biomedical Informatics soon devoted most of an entire issue to papers about the article, some criticizing but most praising.

Though that all took place in 2005, and EHR implementation has jumped significantly since, that work also set in motion Koppel’s career trajectory, stemming from a background in writing about workplace technology use. Today, in addition to teaching, he focuses on the intersection of health-care information technology and patient safety. More specifically, he studies EHRs, both in finding their flaws and creating improvements, as well as cybersecurity, password protection and workarounds used by health-care providers.

“I am actually not a Luddite. I’ve written computer programs; I love computers. I work with computer scientists now,” said Koppel, also a senior fellow at Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics. “But the point was that bad software harms and kills patients, frustrates clinicians, costs society billions and is often not that hard to improve.”

Koppel’s initial EHR research started with a grant to study why young physicians were writing bad prescriptions. The going hypotheses then said it was the expanse of information new doctors had to learn, a lack of sleep, dealing with death and complex illness or some combination of the three. But once Koppel started speaking with first-year residents and poking around in their software, a different picture unfolded, with the software as a central issue.

To do what they needed to do, Koppel quickly learned, doctors had to click through more than a dozen screens, scroll around, look at information in many different computer systems. They received information chronologically on one page, reverse-chronologically on another, denoted by doctor name in one spot and technician name in another. Tests appeared multiple ways, with several different phrases, for example, “lipid panel,” “hypercholesterolemia” and “low LDL,” all indicating the same thing.

“In other words, there was no coherency,” Koppel said.

He interviewed residents and shadowed physicians. The more he spoke with them, the more they revealed. One example stands out all these years later.

One senior resident clicked on the wrong of two “Malones” in the system and ordered what could have been a lethal dose of the diuretic Lasix, which makes a patient urinate. The body becomes used to the drug, so it’s not problematic for someone taking increasing doses. But this person had never before taken it. The patient had had enough liquids that morning to prevent dire consequences, but the incident shook up the resident. That story, which emerged in a focus group, spurred other participants to share their own.

“Because I wasn’t a physician, they would be honest about stuff that they wouldn’t say to one of their senior physicians,” Koppel said. “They were very bright and very concerned. I’ve never met a young doctor, or any doctor, who took errors lightly.”

This holds true today more than ever, he said. And, though a decade-plus equates to eons in terms of technology, poor design and incoherent presentation of information still plague EHRs. Also, unlike the cost of many software programs, which have declined, EHRs cost anywhere from several hundred million to more than a billion dollars, plus several years, for a hospital system to implement.

Of course, not all EHR problems relate to vendor issues.

“In a well-intended but misguided effort to quantify quality of care, we’ve clogged up the EHR” with all kinds of measures that irritate doctors, don’t make them better at their jobs and don’t produce better health care, Koppel said.

Medication errors are particularly scary, he noted, citing a 2014 Food and Drug Administration-backed project of which he was one of several co-investigators from Penn Medicine, along with collaborators from Harvard, Kaiser Permanente, Montefiore Medical Center and the University of Illinois.

“We identified more than 50 screens that were genuinely producing horrible errors in medication prescribing,” Koppel said.

The team, which studied computerized prescriber order entry at five health-care organizations, found problems with several functions, such that providers couldn’t locate the drug they wanted to prescribe. Names of medications were abbreviated or truncated, and physicians often couldn’t order dosages they desired, leading them to use a free-text field.

Such workarounds feature prominently in Koppel’s other research focus today: cybersecurity. Ask him for examples in health care and he rattles them off.

At one hospital in the Northeast, portable workstations automatically log out physicians when they move away from the computer, triggered by a sensor atop the machine. Real-time use, however, showed that physicians frequently leave the machine to interact with patients and other information sources. So, to prevent the computers from logging off, the physicians placed upside-down Styrofoam cups over the proximity indicators.

Another illustration: A 92-year-old patient needs a refrigerated medication, but the fridge is far away, up and down stairs, in a different corridor. Rather than moving the patient, the health-care providers copied the patient barcode and now bring that to the refrigerator. They do this for multiple patients at once, maximizing their efficiency but potentially endangering those they’re treating.

“If you go into a med supply room, you’ll see a forest of yellow stickies with everybody’s work-related passwords, because people need to get their work done and they don’t like being hassled by rules that don’t make sense to them,” Koppel said. “Workarounds are almost always indications of an inefficient system, not a lazy provider.”

In the past few years, Koppel has become something of an expert on this topic, publishing upward of 20 papers on cyber- and password security, speaking at National Security Agency conferences and working directly with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology.

Most recently, he submitted for publication a paper about the plethora of logbooks and journals touted as password notebooks, “the exact opposite of what we recommend,” he said. He’s working with the National Health Service in Great Britain to implement software that allows providers to report problems with EHRs in real time, and he’s helping to build a program that makes data about opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions in the United States more visually accessible.

The ultimate aim with all this research, he said, is to create technology that’s usable and safe in the health-care setting.

“I’m an enthusiastic supporter of this of technology,” Koppel said, “but a lot of the products need serious improvement.”