Linguists at Penn Document Philadelphia ‘Accent’ of American Sign Language

Jami Fisher, a lecturer in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Linguistics, has a long history with American Sign Language. Both of her parents and her brother are deaf, she’s Penn’s ASL Program coordinator and now, with Meredith Tamminga, an assistant professor in Linguistics and director of the University’s Language Variation and Cognition Lab, she’s working on a project to document what they’re calling the Philadelphia accent of this language.

“Philadelphia ASL historically, and I think anecdotally, has always been seen as a little different,” Fisher said. “We’re not really sure why.”

That basic idea planted the seed for asking bigger questions. What differentiates Philly ASL from other such dialects? Why do those in the deaf community have an intuition that it’s different? And how could scientists better understand the regional variation?

“We don’t know much about it beyond the lexical level, which is the equivalent of who says ‘pop’ and who says ‘soda,’” Tamminga said. “People get really excited about it but from a linguistic point of view, it’s fairly superficial. People can learn new words and the words spread.”

Rather, Fisher and Tamminga wanted to dig deeper, basing their research on the way Bill Labov, the former John H. & Margaret B. Fassitt Professor of Linguistics at Penn, studied the area’s spoken language for more than five decades, focusing on subtle and granular changes like how a vowel’s use morphs over time.

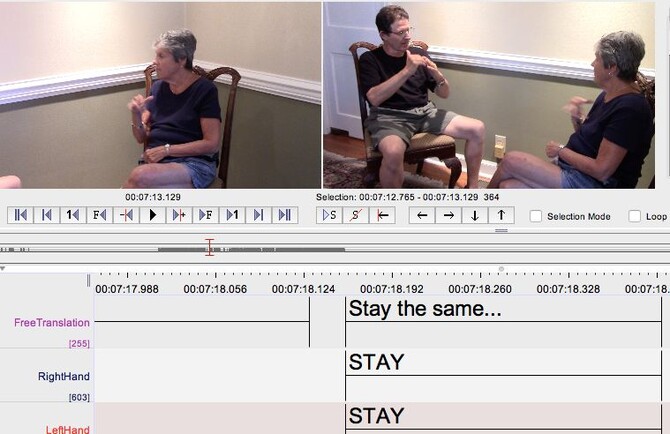

To that end, the pair secured a $10,000, one-year Research Opportunity Grant from Penn’s School of Arts & Sciences to pursue video interviews with 12 in Philadelphia’s deaf community, both young and old, and to get those interviews annotated, a painstaking process that takes up to two hours for every one minute of signing captured. For the project, they’re collaborating with Gallaudet, a university for the deaf and hard of hearing in Washington, D.C.

They’ve also recruited Jami’s dad, Randy Fisher, to conduct the interviews. “Part of the entree that we had, particularly with the older signers, is that my father is part of this community. I’m part of this community too, via my family, but my father knows this community,” Fisher said. “He has lived in Philadelphia for more than 50 years.”

That makes the interviewees more comfortable to communicate freely and tell personal stories about their experiences, not all of which were pleasant.

In the time before the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the first iteration of which came in the 1970s, deaf education looked nothing like it does today. In many cases, children of hearing parents boarded at one of the deaf schools, sometimes starting as young as three, to learn from their peers.

This was the case in Pennsylvania from 1820 until 1984, at which point, “the numbers [at the nearest school for the deaf] were declining significantly because of IDEA,” Fisher said. “That changed the landscape for deaf education significantly.” From then on, many more deaf children went to mainstream schools, where they typically had fewer deaf peers and less exposure to signing; the signing they did see most likely came from an interpreter who was often not a native Philadelphia signer.

“You no longer had this setting with deaf adults in particular, deaf peers, exposing deaf children to the language, but also to these cultural traditions and norms,” Fisher said.

Aspects of the language changed, and that’s what Fisher and Tamminga hope to capture, with the eventual end goal of creating an online resource they plan to make available to the wider community.

“We want to turn this into a corpus that’s publicly accessible,” Tamminga said, “to build a web interface so that anyone can go online to see the videos, the stories, the annotation and timeline.” She offers as examples linguists working on similar corpora or deaf schoolchildren in Philly interested in learning about their heritage.

Though their corpus could be a half-dozen years from completion, Fisher and Tamminga said they plan to publish new findings as they go. The area’s deaf constituency is all for it. “There’s this real pride in how different Philadelphia ASL is,” Fisher said. “Members of the community are saying we need to get this documented, to preserve our heritage.”