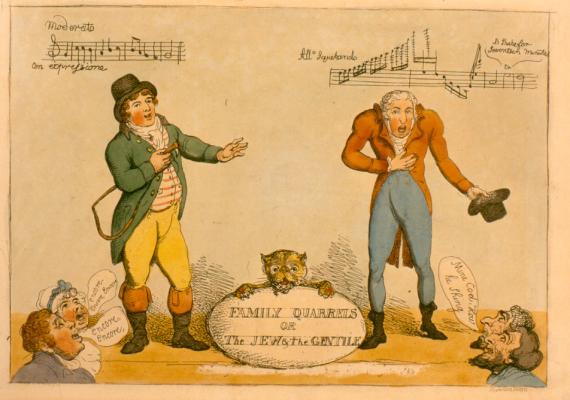

Uri Erman, a cultural historian of Britain and Western Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, focuses his research on performers and group identity, particularly gender, class, and ethnic identity. He has researched how British opera both aided and undermined the acculturation of Jewish vocal artists in the 18th and 19th centuries, and what was unique about Jewish performers’ engagement with the operatic medium.

“Opera was a hotly debated issue in 18th- and 19th-century Britain,” Erman says. “On the one hand, opera was seen as a foreign imposition, a form of aural luxury imported from continental, Catholic Europe that catered mainly to the vitiated tastes of the nobility. On the other hand, there was a growing realization that opera was a marvelous artistic achievement and that there was a need to adapt it into the British cultural sphere. Handel’s biblical oratorios were one way of solving this tension: with their simpler vocal address, set to English texts, and within a devotional frame of reference. However, this development also had a stifling effect, making it ever more challenging to offer ‘secular’ forms of English-language operas.”

Erman also explores the ways in which the public persona of the singer in 18th- and 19th-century Britain persists into contemporary times in the image of the singer today, either in Jewish or English-language contexts

“In the 18th and 19th centuries, the operatic and theatrical spheres were very much centralized, with only a few ‘licensed’ theaters in what was a highly regulated industry,” he says. “Moreover, the periodical press in Britain, although relatively free and uncensored (compared to other parts of Europe), was also very partisan and often explicitly biased toward certain agendas. All this made for a challenging terrain for a singer—or any public performer—to navigate. In the case of the Jewish singers, one gets the sense of a combative public discourse conducted on their backs, imposed upon them, while they had minimal means to interject, limited as they were to their in-auditorium interactions with their audiences. Indeed, we have very little means of knowing exactly how they experienced these dynamics. I think that public performers today are much more liberated in this sense, with multiple ways not only of exploring their identity (including their religious and ethnic identity), but also of controlling its public manifestations.”

Read more at the Katz Center.